Page under construction. After explanatory text there’s a link to the main page of the database. Add photos of “Our Boys” ads plus Mancini photo.

Pittsburgh, PA 15201-0015

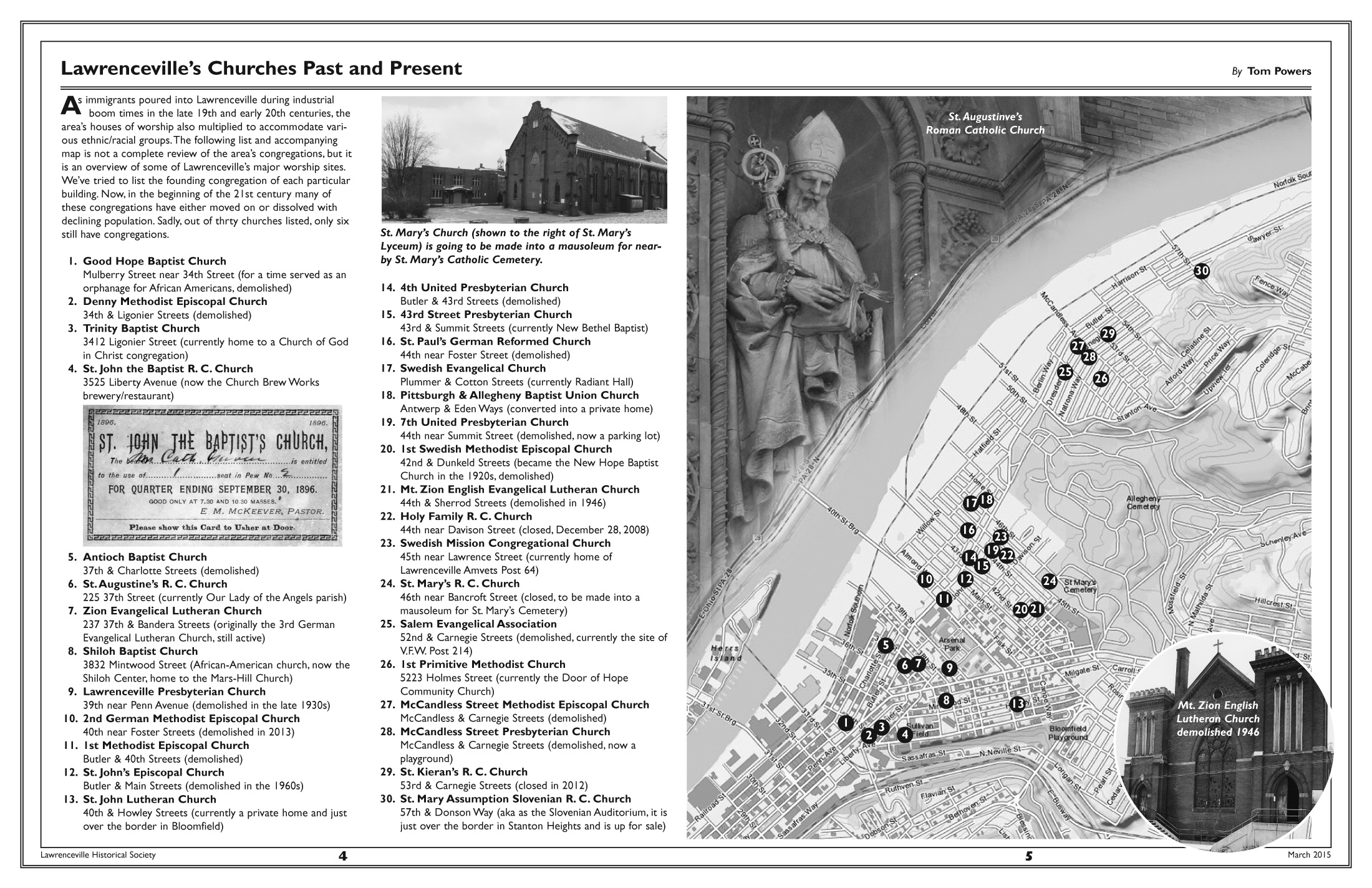

Lawrenceville Churches

43rd (Ewalt) Street Bridge

This article was written by Jim Wudarczyk. It appeared in the December 1993 issue of Historical Happenings the official newsletter of the Lawrenceville Historical Society.\

A historically prominent bridge that no longer stands is the Ewalt Street Bridge or the 43rd Street Bridge, which was erected in 1870 and served the community until the opening of the Washington Crossing Bridge at Fortieth Street in December of 1924. This bridge was a covered bridge, designed by Felician Slataper, that connected Lawrenceville with Millvale. The stone piers on which the bridge set came from the old Freeport Aqueduct when the Pennsylvania Canal was abandoned. These stones were loaded on flats and towed down the Allegheny River, and the stone piers may still be seen at the foot of Forty-third Street.

The Ewalt Bridge Company was formed on March 22, 1869, with a capital of $100,000, raised by selling 2,000 shares of stock at a par value of $50. Huge timbers and planks spanned the stone piers with a cobblestone approach to the bridge. On the Millvale side was a walk with a hand rail for pedestrians that was open so they could look down the river, while the Pittsburgh side was completely enclosed. Inside the bridge was sufficient room for a wagon, a horse and a man to walk. A toll was payable on the Lawrenceville side.

The floor of the bridge was twenty feet above the water, while the enclosed building was fifteen feet high. This structure ended on the Millvale side on a plank road, which ran south to Pittsburgh and on to approximately Grant Street in Millvale. The county purchased this bridge in June, 1912, for $120,000. Upon dedication and opening of the Washington Crossing Bridge in December, 1924, the Ewalt Bridge was sold to Diamond Match Company to be converted into matches.

Face of a Tragedy

This article was written by Tom Powers. It appeared in the December 2018 issue of Historical Happenings the official newsletter of the Lawrenceville Historical Society.

Fredalina (aka Lena, Melinda) Neckerman (1843-1862) was one of the unfortunate girls working in Room No. 1 of the Allegheny Arsenal laboratory when a spark ignited three barrels of gunpowder on the porch in front. The explosion collapsed the roof and killed 22 of 28 girls working in that room. Of the 72 girls/women killed on September 17, 1862, the above photo is currently the only known image of any of the victims. (Click to enlarge.) Tintype photo from the collection of Ryan Conley, used with permission.The LHS has researched and chronicled previously in this newsletter, in the pages of Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, and in Jim Wudarczyk’s 1999 book Pittsburgh’s Forgotten Allegheny Arsenal the disasterous explosion on September 17, 1862, which took the lives of 78 people working in a laboratory building on the upper grounds of the Arsenal property. Our research has located the position of the laboratory building, images of the surviving employees and military personnel, but we had never come across an image of one of the victims. That is until a look into the life of the chief mechanic of the Allegheny Arsenal revealed a secret tragedy in the life of Michael Neckerman.

I had come across an interesting article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch from November 2, 1890, which chronicled the then silent Allegheny Arsenal machine shops and outlined their contributions during the Civil War. Interviewed in the article was Michael Neckerman (1819-1900) who told of his experiences during his time at the Arsenal from 1841 until 1866. The article’s author states that Neckerman was “the constant assistant of Lieutenant Rodman in all his gun experiments” (i.e., the gigantic “Rodman Gun”). When Rodman was transferred to the Watertown Arsenal in Boston, Neckerman was dispatched there as well in 1859. By 1860, Neckerman returned to the Allegheny Arsenal so he could be with his family.

In this Dispatch article there was no indication of the loss Neckerman would suffer once he was back in Pittsburgh. His eldest daughter Fredalina was killed in the September 17, 1862, explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal when three barrels of gunpowder were ignited in front of the laboratory room where she was assembling bullet cartridges. Room No. 1 was closest to the explosion and Fredalina lost her life along with 21 other young girls as the roof collapsed in on the room.

It was not uncommon for employees of the Allegheny Arsenal to have family members working at the facility. In fact, laboratory superintendent Alexander McBride’s daughter Kate was working in Room No. 6 in the laboratory at the time of the explosion when the roof collapsed and killed her. Heroically, McBride continued to assist with other victims, even with the knowledge of his daughter’s death fresh in his mind.

This clipping from an article in the September 20, 1862, Pittsburgh Gazette lists “Melinda” Neckerman as a casualty in Room No. 1. It’s possible that at the time Fredalina was unhappy with her given first name.

I first came across Michael Neckerman’s family while going through the census records on Ancestry.com where the family first appears in the 1850 count. There appeared Michael, his wife Matilda, a 7-year-old daughter Fredalina, and 1-year-old son Irwin. The 1860 census showed that the now 17-year-old Fredalina was going by the name “Lena” and that another daughter, Adelaide, was added. Adelaide was evidently born in 1851, and by the 1870 census, Adelaide was the only child in the Neckerman’s home on 39th Street. The home was located across the street from where the 1866 Officer’s Quarters building still stands today.

Continuing on Ancestry.com, I accessed a couple family trees that had Michael Neckerman in them. This is where I found the photo scan of a tintype attributed to Fredalina. The current possessor of the tintype is Ryan Conley, descended from Fredalina’s sister Adelaide. Also in Ryan’s possession is a diary from Michael Neckerman, written three months before his death in 1900.

In the diary, Neckerman wrote the following about the family tragedy: “Our oldest daughter, Fredalina, who was engaged to a brave young man, saddler by trade, lost her life in the terrible explosion of the powder magazine in the Arsenal on September 17, 1862. One hand was found on which was the engagement ring by which it was identified, and was buried in Allegheny Cemetery with seventy-four other unfortunate young ladies (final count is 78 deaths, 72 of which were girls/women –ed.). Her intended, William Körning, through grief, enlisted in the army and lost his life in a battle in Virginia. That was the hardest blow that ever befell us, although there is some consolation in knowing that they both died for their country.”

The above quote was translated from the German by William Miller, Jr. (1884-1920), Michael Neckerman’s grandson.

So far, Fredalina’s is the only image we have of an Allegheny Arsenal explosion victim. Hopefully there are other photos out there that can help memorialize those lost in this tragic accident.

Sources

Stofiel, L. E., Pittsburgh Dispatch, “Where Death Began,” November 2, 1890, p. 17.

Pittsburgh Gazette, “The Explosion at the Arsenal,” September 20, 1862, p. 4.

Neckerman, Michael, Diary, March 1, 1900, translated from German by William L. Miller, Jr. (1884-1920).

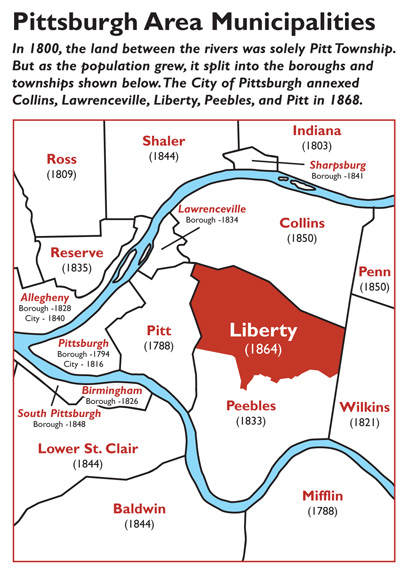

Liberty, the Mysterious Township

This article was written by Tom Powers and Jim Wudarczyk. It appeared in the December 2018 issue of Historical Happenings the official newsletter of the Lawrenceville Historical Society.

Prior to the American Civil War, the City of Pittsburgh consisted of approximately nine square miles and incorporated what we now know as Downtown, the Hill District, and part of the Strip District. Beyond those scant boundaries were a number of small villages and rural townships.

Prior to the American Civil War, the City of Pittsburgh consisted of approximately nine square miles and incorporated what we now know as Downtown, the Hill District, and part of the Strip District. Beyond those scant boundaries were a number of small villages and rural townships.

When Helen Wilson, vice president of the Squirrel Hill Historical Society, asked the Lawrenceville Historical Society if we had any information on a “Liberty Township,” it set off a search to identify some of the villages, boroughs, and townships that eventually comprised some of the East End neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

In tracing some of the municipalities that eventually comprised many of the eastern communities of Pittsburgh, one finds that neighborhoods like Lawrenceville, East Liberty, Garfield, Point Breeze, Shadyside, Bloomfield, and Squirrel Hill were formerly part of Pitt Township. In Annals of Southwestern Pennsylvania Volume 1, Lewis Clark Walkinshaw gives a vague description of the boundaries of Pitt Township. He indicates, “Pitt Township was named for Fort Pitt, and was the municipality bounded north and west by the Allegheny and Ohio.” Over time, Pitt Township was reduced several times.

One township carved from Pitt Township was Peebles. Court dockets indicate that it was incorporated November 26, 1833. Wikipedia shows four maps under Collins Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Based on these maps, it appears that Peebles encompassed a large geographic area that ran from the borders of the city, Lawrenceville, and the remainder of Pitt Township on the west to the current city line on the east. It also extended from the Allegheny River on the north to the Monongahela on the south.

Lawrenceville Borough split off from Peebles on February 18, 1834. The boundaries were smaller in comparison to the area that we know today. Our story and map about the borough appeared in the March 2017 newsletter.

Just beyond Lawrenceville was the village of Hatfield, which was conceived by George A. Bayard as a real estate venture. Hatfield was located on Butler Street between 48th and 49th Streets. Writing in the April 1926 issue of the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, P. W. Siebert noted that George A. Bayard owned land across the Allegheny River and lived in what is now a part of the Allegheny Cemetery near the site of the soldiers’ plot.

Collins Township was created from the northern portion of Peebles. The township was named for a prominent lawyer named Thomas Collins, who acquired a portion of George Croghan’s extensive landholdings. George T. Fleming’s History of Pittsburgh and Environs, Volume 1, shows the boundaries as the Allegheny River on the north to Negley’s Run on the east to the Greensburg Pike (now Penn Avenue). This encompassed the old Eighteenth and Nineteenth Wards, which corresponds to the present Ninth and Tenth Wards of the City of Pittsburgh.

As for Liberty Township, there was nothing to indicate its presence until LHS secretary Phil Weber, an avid researcher of Pittsburgh’s East End, noted that Liberty School in Shadyside was probably named for the former township. He was convinced that the township disappeared in 1868 when the City of Pittsburgh underwent a major expansion.

Thanks to the help of LHS member Michael Murphy, a records specialist for Allegheny County, the books in the Court House were located that showed that Liberty Township had indeed existed. Based on the documents, we were able to determine that the municipality had existed only for two-and-one-half years. It was formed from Peebles Township and was incorporated on December 3, 1864. The records show that the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania accepted the request for the creation of the new township based on the fact that there were a sufficient number of voters residing within the boundaries of Peebles Township to justify partitioning it into two municipalities. The boundaries were readjusted on July 28, 1866, when Mr. James Murdoch and others petitioned the Commonwealth, as several of their farms were partly in Peebles and partly in Liberty. The petition requested that their landholdings be included in Liberty Township.

Boundaries of Liberty Township incorporated East Liberty below Penn Avenue, Friendship, Shadyside, and parts of Bloomfield, Point Breeze, Regent Square, and Squirrel Hill.

On April 6, 1867, an Act of Assembly by the Pennsylvania legislature gave approval to the City of Pittsburgh to annex the surrounding municipalities of Collins, Liberty, Peebles, Pitt, Oakland, and Lawrenceville. Later that year those communities voted to approve the consolidation. (Allegheny City was also part of the consolidation effort, but their voters refused the annexation, which would ultimately happen in 1907.)

Consolidation was finalized on June 30, 1868, and Liberty Township ceased to exist as the area became the 20th and 22nd Wards of Pittsburgh. Today the area is known as the 7th and 8th Wards.

During its short existence, one finds a number of prominent Pittsburghers residing in Liberty Township. The following eight township residents are those we highlighted on the Liberty Township map (click on map to enlarge). Capt. Charles W. Batchelor (1823-1896) — Started his career piloting steamboats and eventually started building them. After 1855 he came ashore and became involved with marine and fire insurance as well as banking in Pittsburgh. By the end of his life he also had interests in the oil and gas industries. Batchelor married into the Vandergrift family, who also got their start on the river.

Capt. Charles W. Batchelor (1823-1896) — Started his career piloting steamboats and eventually started building them. After 1855 he came ashore and became involved with marine and fire insurance as well as banking in Pittsburgh. By the end of his life he also had interests in the oil and gas industries. Batchelor married into the Vandergrift family, who also got their start on the river.

Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) — On his way to becoming the richest man in the world, Carnegie owned a house (dubbed “Fairfield”) on Penn Avenue from 1861 until he moved to New York City in 1867. He turned the house over to his brother Thomas, who with his wife Lucy, raised nine children there. Lucy was the daughter of their neighbor William Coleman.

William Coleman (1808-1878) — Coleman worked as a bricklayer until he went into the carriage spring business, which led into iron manufacturing. He later owned vast coal mines in Illinois and manufactured coke. He was one of the first men to recognize the value of the Bessemer steel process. His business and family connections with the Carnegie brothers (see above) added to his fortune. Coleman in 1865 bought the estate of Judge William Wilkins for whom the neighboring township was named. Until it was razed in 1924, the Wilkins’ mansion “Homewood,” stood near the corner of Dallas and Penn.

William Frew (1826-1880) — Started out in the grocery business, but in 1859 he formed a partnership with Charles Lockhart to produce and refine petroleum. The company of Lockhart & Frew built the first Pittsburgh refinery, the Brilliant Oil-works, near Negley Run on the Allegheny River. The company became one of the founding members of the Standard Oil Company in 1876. Frew was connected with several other businesses but he was best known to Pittsburghers as a public speaker on a variety of subjects. He attained the rank of major serving with the 15th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Militia during the Civil War. His home “Beechwood” gave its name to the boulevard that snakes its way through Pittsburgh’s East End.

Thomas M. Howe (1808-1877) — Served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1851-1855. Howe was a delegate to the 1860 Republican National Convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln as the candidate for president. During the Civil War he was chairman of the Allegheny County committee for recruiting Union soldiers. Howe started out in the dry goods business, but eventually branched out into banking and steel. He was the first president of the Pittsburgh chamber of commerce. He was an original incorporator and president for 30 years of Allegheny Cemetery.

Judge Christopher Magee (1829-1909) — A native of Pittsburgh, Christopher Magee graduated from Philadelphia’s University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1852. He returned to Pittsburgh and set up a law office downtown at Liberty and Wood Streets. Magee was appointed Judge of the Court of Common Pleas in 1885. His cousin was Christopher Lyman Magee, notorious political boss of Pittsburgh during the latter half of the 19th century. Judge Magee was one of the corporators of Shady Side Academy as well as Allegheny Cemetery and Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. His former home was located on today’s Carnegie-Mellon campus.

James B. Murray (1818-1884) — His name lives on today as the eponymous avenue that runs through Squirrel Hill’s shopping district. [The road was probably named for his father Magnus M. Murray (1787-1838) who was twice mayor of Pittsburgh and nephew of William Wilkins.] James B. Murray worked for the Sligo Iron Works of Pittsburgh. A clerk by trade, he was also involved in banking. At one point he was the president of the Exchange Bank. Murray’s nephew who resided with him for a while, George W. Guthrie, married neighbor Thomas M. Howe’s daughter Florence. Guthrie would later be mayor of Pittsburgh from 1906 to 1909 and ambassador to Japan from 1913 to 1917.

James S. Negley (1826-1901) — Achieved the rank of Major General during the Civil War and he played a key role in the Union victory at the Battle of Stones River. His varied career ranged from horticulturist, railroader, and U. S. Representative from Pennsylvania. A scion of the well-connected Negley family, his aunt Sarah married Thomas Mellon. During the 1877 Railroad Riot, Negley served as commander of the militia organized by the city of Pittsburgh to maintain order.

Robert Pitcairn (1836-1909) — Born in Scotland, he headed the Pittsburgh Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad in the late 19th century and was the brother of the Pennsylvania Plate Glass Company founder, John Pitcairn, Jr. Robert and fellow Scot Andrew Carnegie worked their way up the P. R. R. corporate ladder. He was also a friend and financial backer of George Westinghouse. The borough of Pitcairn was named in his honor. Pitcairn was responsible for sending the first relief train to Johnstown to assist flood victims in 1889.

William Wilkins (1779-1865) — Wilkins served as the second for Thomas Stewart in the last duel fought in Pittsburgh. The confrontation between Stewart and his rival, Allegheny County Prothonotary Tarleton Bates, left Bates dead. Subsequently, Wilkins worked diligently to become one of the most civic-minded men in Pittsburgh. He was active in both banking and politics. Wilkins served in all three branches of the government: as a federal judge, as a member of both the House and Senate, and in the executive branch (Minister to Russia, Secretary of War).

While the mystery of Liberty Township has been solved, this municipality—like so much of early Pittsburgh history—deserves further study.

Sources

Walkinshaw, Lewis Clark, Annals of Southwestern Pennsylvania Volume 1.

Miscellaneous Docket #1, Allegheny County Quarter Sessions from March 1852 to December 1866, pp. 425, 555, 556.

October 1926 issue of the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, P.W. Siebert.

Fleming, George T., History of Pittsburgh and Environs, Vol.1.

G.M. Hopkins, Co., Atlas of Allegheny County 1876, 1988 reprint.

Morris, Sue, The Historical Dilettante, “How Does Pittsburgh Remember Andrew Carnegie?” blog post, May 9, 2014.

Capt. Charles W. Batchelor, Riverboat Dave’s Paddlewheel Site, www.riverboatdaves.com.

“William Coleman, His Sudden Death Yesterday Morning,” , November 27, 1878, p. 4.

The Arsenal Tunnels

This article was written by Jude Wudarczyk. It first appeared in the March 2002 issue of Historical Happenings the official newsletter of the Lawrenceville Historical Society. It was reprinted in the June 2018 issue with new information. Photos, courtesy of Allan Becer, have been added to this webpage that did not appear in the 2002 article.

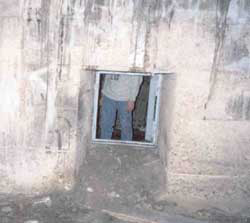

Tired but excited over their adventure, the LHS explorers pose outside the entrance of the famed “Arsenal Tunnels.” From left to right – Allan Becer, Jude Wudarczyk, Mary Johnston, and Rich Bassett. (Photo by Mark Sachon)

Ever since I was a boy growing up in Lawrenceville I heard stories about the tunnels that ran parallel to 40th Street. Many speculated that they were part of the old Allegheny Arsenal. Others guessed that their purpose was to smuggle goods or slaves from the riverbank to a safer haven. There were many descriptions of the tunnels. Some had them starting at the Allegheny River and continuing as far as Penn Avenue. Others had reported other starting or ending points.

No one would claim to have actually been in the tunnels themselves. They all knew someone else that made the mysterious underground trek. This led some of us at the Lawrenceville Historical Society to believe that the mysterious Arsenal Tunnels were nothing more than a giant hoax.

However, when two individuals, Frank Novosel and Bill Schivins, reported that the entrance was in the County Maintenance Department Complex under the 40th Street Bridge I decided to make an inquiry at the department office. I spoke with several of the workers and received information that was so similar to that provided by Frank and Bill that I could no longer believe that there was nothing to the legends. After receiving official permission to set up an exploration of the tunnel I made arrangements to have an experienced tunnel and cave explorer, Mark Sachon, co-author of Urban Blight, a Rock Climber’s Guide To Pittsburgh, make a preliminary journey through the Arsenal tunnel and report back his findings. Mark was happy to do this for us, and provided his services without charge to our society.

Entrance – viewed from inside looking out. Mark Sachon is standing by the door. (Photo by Allan Becer)

Mark’s report was astounding. Not only was the tunnel relatively safe for an inexperienced tunnel explorer such as me, it was obviously not a tunnel at all. More like a honeycomb of rooms, the mysterious area called for further exploration and a second trek was set up to take place on Friday, December 14, 2001.

Having already gone through, Mr. Sachon kindly agreed to lead the second excursion. Bill Siebert and Jack Grant provided access. Joining Mark and me were LHS Board members Mary Johnston and Richard Bassett and local historian and LHS member Allan Becer, co-author of Monster on the Allegheny…and Other Lawrenceville Stories.

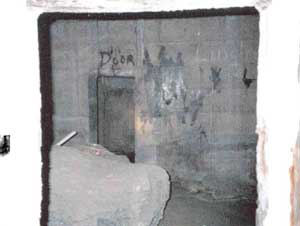

The entranceway to the rooms is a tiny crawl space measuring three feet by three feet and runs about three or four deep. It is covered by a steel grate, which is kept locked to deny access to unauthorized persons. Navigating the entrance is a difficult task, but once having accomplished this fete one is immediately greeted by a large room measuring approximately ten feet by ten feet. This chamber is estimated to be about twelve feet high.

This chamber has a massive concrete slab in it. The slab is much too large to fit through the doorway. (Photo by Allan Becer)

The chamber had a circular layout, which was filled with dirt. It may have been a sewer. (Photo by Allan Becer)

If you traverse a more or less straight line there are twelve more such chambers for a total of thirteen. For sake of convenience I will refer these chambers as the central chambers. Each central chamber has another chamber off to its right and left, which I will call secondary chambers. Some secondary chambers then have yet another chamber beyond it. These will be called auxiliary chambers.

There is no sign of electricity in the honeycomb, but pipes pass overhead and exit without providing any evidence that they have a function within the chambers. Obviously, they are just passing through and possibly provide water and/or gas to the buildings on 40th Street or the Arsenal Terminal. As we progressed inward the ceiling got lower, and we had to be very careful not to bump our heads. I believe that only one of these pipes was oblong in shape and the others were round.

The rooms were filled with graffiti and debris. Obviously, the construction matched that of the bridge, and not the Arsenal. The chamber walls were made of concrete. In places they were beaded with water, as was the ceiling. Occasional stalagmites and stalactites were visible. In spots rusted steel cables poke through the walls some of which have wooden blocks at the end of them. Despite the moisture on the walls and ceiling the rooms are very dry and dusty.

The doorways passing from one chamber to another required us to stoop. Only the central chambers have doorways connecting them to the next set of chambers. There were no signs of life in the chambers save for one set of tiny footprints and two spiders. Sounds of traffic could be heard overhead in the first few chambers, but then was lost only to be heard again near the end of our tour.

The dust floor gave way in spots revealing occasional brickwork on the floor, which suggests to this author that we were walking along what was once the sidewalk of 40th Street. It is known that in the 1920’s while the bridge was being built, the street was shifted to allow for the construction. According to some reports a few of the buildings on the opposite side were lifted and pushed back.

This portion of a tunnel servicing the Allegheny Arsenal was found during the 2001 exploration. Given the dimensions of the tunnel, we know exactly what it was used for. Read on to the end of this article. (The above photo by Allan Becer is a composite of two. You can see the seam in the center.)

About midway through the excursion we came across one room where the floor had collapsed revealing a tunnel of sort about four feet wide and five and a half feet high. It was oblong on three sides with an arched ceiling, and looked very much like it might have been part of the Allegheny Arsenal at one time. Only about seven or eight feet of this tunnel is visible. Allan Becer speculated that it was part of an old sewer system. I feel that it is the remains of an old hallway belonging to a building. It must be remembered that sewers are usually far below ground level, and the chamber floor was more or less ground level. The exposed tunnel was not very far beneath the surface of the chamber floor hence I feel it is unlikely to have been a sewer. However, only further investigation will settle the issue. *

Later that day Allan found out large structures such as university buildings and bridges often have these honeycombs, which serve as part of the superstructure. An architect told him that the purpose of these honeycombs is twofold. First and foremost, they are just as strong of a base as if a solid concrete slab. As they use a lot less concrete they are a lot more economical than a solid slab. Second, they serve as a dumping ground for unwanted building material, which would explain a lot of the debris we saw.

Although this is a very logical explanation,it does not explain why there are doorways connecting the chambers. Nor does it explain why there are steel cables protruding from some of the walls or why some of these cables have wooden blocks on the ends. While some questions remain, we now know that the legendary Arsenal Tunnels do exist even if they aren’t part of the Arsenal, aren’t tunnels and don’t run from the riverbank to Penn Avenue.

___________

* Further investigation has found a likely answer to Jude’s speculation. While researching the construction of the Allegheny Arsenal, I came across a section of the 1859 Ordnance Department Report to the Secretary of War. The report on the Allegheny Arsenal (shown here is part of page 1121) states that a tunnel was dug from the river to the machine shop’s steam engines to supply them with water for their boilers. The machine shop was located right along 40th Street near where the bridge ramp is now positioned. Jude’s measurement of the exposed tunnel shown in the above photo, four feet wide and five and a half feet high, corresponds with the measurements given in the report. – Tom Powers

Lawrenceville’s Oldest Photo

This just may be the oldest photo taken of the Lawrenceville landscape. The photo was shot by William T. Purviance who had a photography studio at the corner of Diamond and Market Streets in Pittsburgh from 1859 to 1867. The Pennsylvania Central Railroad hired him to do a series of scenic views of the areas it served. This shot of the Allegheny Arsenal’s Butler Street gatehouse was probably taken circa 1868 when he began the series. The photo is one side of a stereoview and the full card is shown below.

Allegheny Arsenal Photo Map

Allegheny Arsenal 1862 Explosion

Lawrenceville Borough (1834-1868)

This article was written by Tom Powers. It appeared in the March 2017 issue of Historical Happenings the official newsletter of the Lawrenceville Historical Society.

These days, not many Pittsburghers realize that once upon a time Lawrenceville was an independent borough outside Pittsburgh’s city limits. I had never seen the drawn boundaries of Lawrenceville Borough until I attended a lecture in the Heinz History Center’s Detre Library about an 1859 panoramic map of Pittsburgh.

Lawrenceville Borough was formed out of Peebles Township in 1834. Peebles had been erected a year prior to that out of Pitt Township. Collins Township was formed out of Peebles in 1850. Collins, Lawrenceville, Pitt, and Peebles were all consolidated into the City of Pittsburgh in 1868.

On display were several other maps including an 1862 map of Allegheny County from which the map on this page is taken. On this map, the borders of Lawrenceville Borough were clearly defined.

Our LHS collection includes a copy of the laws and ordinances of the borough from 1834 to 1863. Among the ordinances are the boundaries of the borough at its later expansions. Unfortunately, the description of the borders in the ordinances includes some landmarks that are long gone, for instance:

… west one hundred and twenty-five and three fourth poles*, (crossing Covington street at forty-three and three fourth poles, and Pike street at eighty-five and one fourth poles) to a post; thence south forty-one degrees, west ninety-eight poles, to a large button wood tree, (a well known land mark) on the bank of the Two Mile Run… (Laws of the Borough of Lawrenceville).

* A pole equals sixteen and a half feet.

Well, that large buttonwood tree is long gone, and Two Mile Run has been piped underground. These survey points are of little use in trying to recreate Lawrenceville Borough boundaries, so it was a stroke of good fortune that a contemporary (1862) cartographer was able to draw up the borough.

Originally, the northeast boundary of Lawrenceville Borough was roughly along the line of today’s Main Street or “beginning at a large soft maple tree in front of Samuel Ewalt’s land” (long gone). The borough expanded up to 48th Street in 1844 and then up to 51st Street in 1852. Interestingly, neither Allegheny Cemetery nor St.Mary’s Cemetery were ever within the borough’s boundaries.

As population grows, municipalities are stressed to perform services within their borders. This is why certain neighborhoods or communities would petition the state of Pennsylvania to form a municipality with more manageable borders. Partly because of its topography, Allegheny County currently has 130 municipalities, the most in the state. Luzerne County is second with 76 municipalities.

Today, Lawrenceville is divided into three sections within the City of Pittsburgh (which annexed the area in 1868): Lower (part of the 6th Ward), Central (9th Ward) and Upper (part of the 10th Ward). Taken together, they stretch along the Allegheny River from 33rd Street to the Sharpsburg bridge (technically 62nd Street).

If anyone can find traces of the large buttonwood or soft maple trees, let us know.

(From the LHS newsletter Historical Happenings, March 2017)

Sources

W. B. Negley, “Allegheny County; its Formation, its Cities, Wards, Boroughs and Townships,” Atlas of the County of Allegheny, Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins & Co. , 1876, p. 4.

Map of Allegheny County, Philadelphia: Smith, Gallupp & Hewitt, 1862, www.loc.org

Map of Allegheny County, Philadelphia: Sidney & Neff; Allegheny City: S. Moody, agent, 1851, www.loc.org

Laws of the Borough of Lawrenceville, Allegheny County, PA., Acts of Assembly, Supplements Thereto, and Ordinances Passed by the Burgess and Town Council, Pittsburgh: Barr & Myers, 1863.